To All the Artists I've Loved Before

- Gerriann Brower

- Jun 2, 2018

- 9 min read

Updated: Jun 22, 2022

I owe my passion for art history to a Catholic Missal and babysitting. My earliest art memory took place during Mass as I paged through my father’s Saint Andrew Bible Missal. The page edges shined with gold and inside were colorful reproductions of the Madonna, Jesus, saints and sinners. I gravitated towards the art, not quite sure what the art meant, how it was made or who made it. The colors, gold backgrounds, deep linear outlines of figures with large eyes, intricate designs and what I now recognize as a Byzantine style fascinated me as a nine-year-old.

I still have the Missal and think the art is wonderful: miniatures from a Benedictine German thirteenth century manuscript. Without a doubt the Catholic church has long been a patron of great painting, sculpture and architecture that is inspiring and beautiful.

The Ascension, MS 9222, Benedictine Abbey of Saints Martin and Eliphus, Cologne, early 13th century, Bibliotheque Royale, Brussels, reproduced in the Saint Andrew Bible Missal, DDB Publishers, 1962.

A door opened wide to the study of art by happenstance. I was in high school babysitting two kids across the street from our house while the parents stayed out quite late, way before cable, wi-fi, or smart phones. The kids were asleep and I was viewing the limited TV channels available after 10:00 p.m. The late-night TV re-run movie starred Kirk Douglas in “Lust for Life.” The 1956 movie, based on the historical fiction novel by Irving Stone, featured the life story of Vincent van Gogh. Kirk gave a forceful and energetic portrayal of the Dutch artist complete with Vincent’s artistic brilliance and tortured existence.

Gateway Artist

Despite the over-reaching film, and reliance on clichés of the lonely tormented artist, it sparked an interest in this Vincent guy and I had to find out more. The library led me to a new world of van Gogh and the Impressionists. I began to form a sense of his oeuvre, where he painted, when he lived, his contemporaries, and the loving letters exchanged with his brother Theo. Vincent was my gateway artist that led me to Paul Gaugin and Paul Cezanne, which led to exploring the Impressionists: Monet, Manet, Degas, Renoir, Pissarro, Cassatt and Singer Sargent. Art after Vincent? Cubism, Expressionism, Surrealism and the other “isms” with Picasso, Leger, Matisse, Munch, Dali, etc.

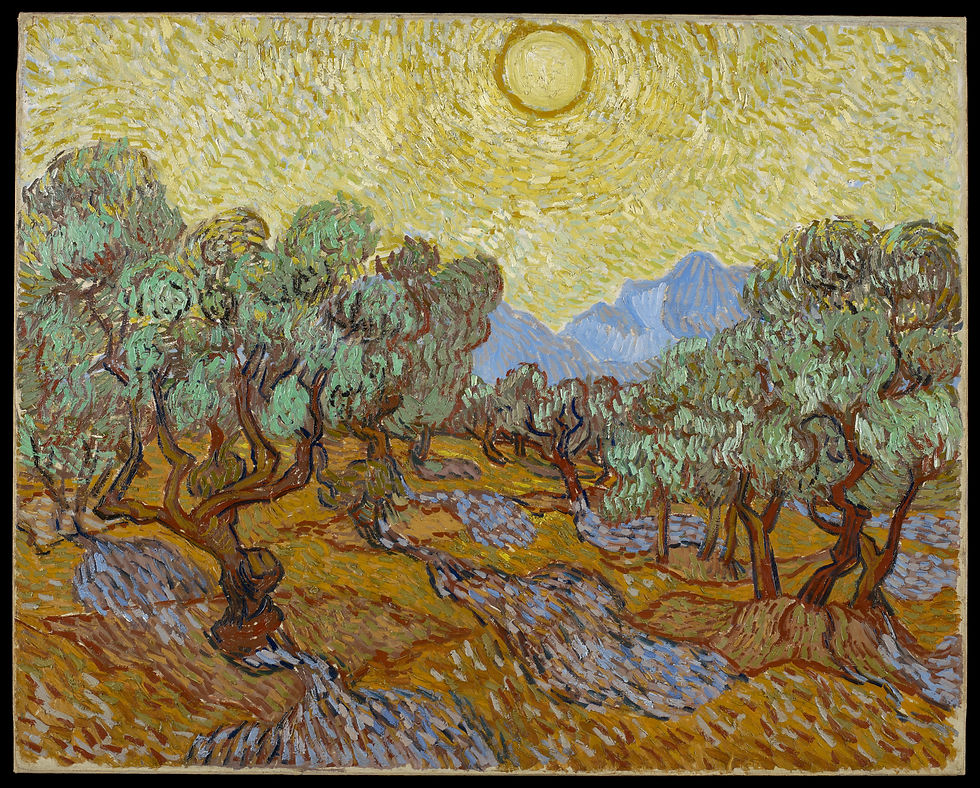

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees,1889, Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Vincent was my art history keystone. His vibrant color, thick impasto, the way he captured the movement of nature, the everyday people he painted, and his inability to socially connect or sell his art, all captured my interest. I was thrilled to see van Gogh in person at my hometown Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Much later, I fulfilled all my van Gogh dreams with visits to the Amsterdam van Gogh museum and the Kroller-Muller Museum in the Netherlands.

Beyond Vincent

I was hooked with my first Art History classes at the University of Minnesota. I fell for many artists after Vincent and this post highlights some of my Italian art loves. The inspired teaching of my Renaissance-Baroque professors instilled in me more than affection for these artists. I learned how to conduct research, fundamentals of writing, deep observation, and how art is inexorably a reflection of social, political and economic history. From the graceful ornate elegance of the 1400s, to the classic figural compositions of the 1500s, beyond to the dramatic action of the 1600s, Italian art has never ceased to captivate me. Here are five that I particularly admire.

Some of my art books collected over the years.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini

Independent study in Rome as an undergraduate art history major - what could be better? I jumped at the chance to design my own study on Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the seventeenth century sculptor and architect. I was quite taken with his dramatic flair and contrast to 1500s art. The sixteenth century valued order and stability; think of Michelangelo’s David, Leonardo’s or Raphael’s Madonnas and child paintings. Their figures are monumental, solid, often understated, and contemplative. Triangular compositions were common and figures expressed controlled emotion. Bernini’s art is in motion, twisting, turning, surprising. Figures are depicted in the middle of a dramatic moment. It was a different era – the Baroque.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, David, Borghese Gallery, Rome, public domain photo Pixabay. Sculpted 1623-4, David stands at 5’7”.

One of the last great Italian artistic talents to master multiple mediums, Bernini dabbled in painting, city planning, stage designing and playwriting. He left an indelible mark on Rome, from fountains to St. Peter’s Basilica. He is responsible for the Baldacchino with four twisting columns, interior sculptures, and the exterior colonnade. Florence was the artistic focal point in the 1400s and early 1500s. Then Rome became the hot spot for artistic creativity, especially under the dominant patronage of popes and cardinals.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Baldacchino, St Peter’s, Rome. 1624-33. Bronze and gilt. The Baldacchino stands over the high altar. His ingenious design provides a focal point for the enormous church without disrupting the sight lines through the apse to the chair of St. Peter.

Bernini’s David, although a tiny mite compared to Michelangelo’s version, twists as he prepares to launch his rock that will slay Goliath. Michelangelo’s David stands firm, glaring, maybe thinking about his opponent. Michelangelo emphasizes muscle while Bernini chooses the moment of battle. Bernini’s statue is like a split-second snap shot, depicting David’s face taunt with the fierce physical effort necessary to down the giant.

The textures of David’s tousled hair, shepherd’s pouch, discarded armor, and rough sling rope contrast to his smooth lean limbs. Compared to Michelangelo’s David, Bernini’s is a slight youth. I was impressed that I could look David in the eyes and feel his strength and presence. One looks up to Michelangelo’s David; one wants to duck to miss Bernini’s David slinging the rock.

Simone Martini

The first time I saw Simone Martini’s Annunciation in Florence’s Uffizi projected onto the screen of my art history class it grabbed my attention. The gold, ornamentation and the simplicity of design took me with the same awe as looking at the Missal in the church pew. I developed a deep fondness and respect for all things Siena from my art history class to eventually visiting the city. What I like most about Simone’s art is that he is a metaphor for Siena. He is truly Sienese in style and form. Although today about one hour and twenty minutes from Florence by car, it is a world away from Florence today as it was in the fifteenth century.

Siena stood their ground culturally and in warfare against their Florentine arch enemies for hundreds of years, and artistically Siena tended to reject the newfangled Florentine representations of perspective or naturalism. Fifteenth century Sienese art is mystical, transcendent, and ornate. The Sienese believed religious art is devotedly spiritual. The Madonna is no ordinary woman and shouldn’t be depicted as such. She should have a halo, preferably on a throne, and represented in a heavenly setting, not depicted sitting on the ground in Tuscany.

Simone Martini, Maesta’, Palazzo Publbico, Siena, 1311-17. The Madonna and saints oversee the Council Chamber with inscriptions

that advise wisdom and justice.

Learning about Siena, and their inherent cynicism of anything Florentine, broadened my perspective about Renaissance art. Florence defines the Renaissance for many tourists but the Renaissance is much bigger than one city. I love that the Sienese maintained their cultural heritage and proudly went their own way.

Martini was prolific in fresco and panel paintings. One of my favorites is the large Maesta’ fresco in the Siena Palazzo Pubblico. The fresco commands the room at nearly 25’ x 32’. Surely the city council members found it impossible to govern without thinking of the watchful eyes of the many saints, Madonna and child.

The Madonna’s drapery is delicately and intricately painted with blue geometric patterns trimmed with gold. Simone’s technique evokes the tactile sense of a fine silk. The end result is charming and powerful. I have always found that art in situ (in its original place) packs more punch than hanging in a museum. Each time I visit Siena I pay homage to Simone and his Madonna. I love it as much now as on my first visit.

Simone Martini, Maesta’, details, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, 1311-17.

Fra Angelico

A recent trip to Tuscany consisted of seeking out all the Fra Angelico’s I could find. I was smitten with the color and aura of his paintings. A Dominican friar, Fra Angelico was a transitional artist in Florence during the first half of the 1400s. Transitional in the sense that he bridged different styles, introducing natural light, figurative realism, compositional harmony, and recognizable Tuscan landscapes in the background, while true to tradition using lots of gold and ornament.

Fra Angelico’s Florence was a city of poverty, frequent outbreaks of plague, and unstable government. Artistic tradition was often preferred to innovation. He gently incorporated pioneering elements.

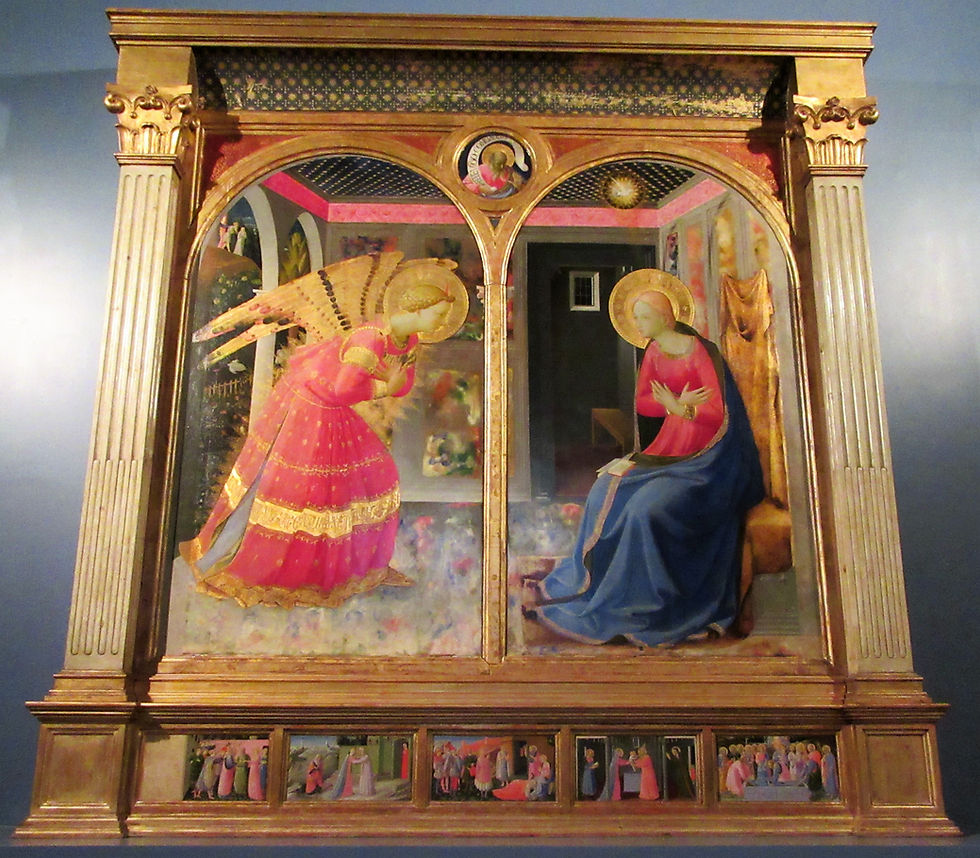

Peaceful yet powerful elegance defines Fra Angelico’s paintings. The vibrant colors in the Annunciation altarpiece from Santa Maria delle Grazie in San Giovanni Valdarno pop with pink, gold, and blue. Angelico’s scenes always emanate grace and refinement with calm and dignified figures.

The clarity of color was more evident in person than in a book or on a screen. The gently falling pink and gold fabric of the angel is exquisite as are the gold colored wings which alight to announce to Mary that she will carry the son of God.

Fra Angelico, Annunciation, Museo della Basilica di Santa Maria delle Grazie, San Giovanni Valdarno. 1430-32.

Fra Angelico, Annunciation, details, Museo della Basilica di Santa Maria delle Grazie, San Giovanni Valdarno. 1430-32.

Michelangelo

Readers of this blog will not be surprised I admire Michelangelo. I have always leaned towards Michelangelo, although I respect all the Renaissance greats. I find Raphael a bit too sugar sweet, Leonardo with too many unfinished paintings and too much daydreaming writing backwards in notebooks, but with Michelangelo’s oeuvre in painting, sculpture and architecture over a long productive life time, there is a lot to admire.

The power expressed in his figures is the exact opposite of Fra Angelico’s delicacy. Michelangelo gets right to the point, minimizing any background or scenery. It’s all about the figures telling a story. His cantankerous personality plus loads of documentation in letters and finances gives us a clear picture of the man.

Michelangelo, David, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence. 1501-4.

Seeing the iconic David for the first time remains this art history student’s highlight of my first trip to Florence. Colossal in size, the technical expertise needed to carve an old block of marble that someone else had started and abandoned says a lot about his drive and nerve.

Caravaggio

Caravaggio’s dramatic intensity changed painting and influenced many European artists such as Rembrandt. Walking into the smallish and unassuming Santa Maria del Popolo (St. Mary of the People) in Rome, situated on the northern edge of the Roman wall, I thought there’s not much to the outside. A wealth of art treasures awaited me inside.

The small Cerasi Chapel has two Caravaggio paintings, the Conversion of St. Paul and the Crucifixion of St. Peter. The impact of seeing Caravaggio in situ for the first time is analogous to having a black and white TV and getting your first color TV. Caravaggio’s paintings are great in museums but to see them in Santa Maria del Popolo is remarkable. Even the photos don’t them justice because they are taken straight on and not at an angle in the space for which they were created. These paintings would loose a lot of their impact if they were in a museum.

Caravaggio, Conversion of St. Paul, Cerasi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome. C. 1601.

Figures in the compositions are strikingly foreshortened to maximize the impact from the side as one enters the chapel. Paul’s horse takes up a large portion of the oil painting, which seems to take place in the dark. Unlike previous paintings of the subject which emphasize the action of falling off the horse in sudden surprise, Caravaggio highlights the drama of conversion with light and dark and a uncluttered composition with Paul’s arms forming an upward “V” towards the light. He eliminates anything unnecessary to maximize the pivotal moment.

Caravaggio, Crucifixion of St. Peter, Cerasi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome. C. 1601.

Caravaggio’s dramatic use of light and dark, called chiaroscuro, along with an economy of composition differentiated him from other artists. Known as a rogue personally and professionally, he didn’t make many, if any, preparatory drawings, he walked around Rome brandishing a sword, got into trouble with the law, and generally rejected customary artistic processes and social graces.

Despite his behavior and because of his revolutionary way of painting, Caravaggio was a sought-after painter in Rome. However, in 1606 he fled Rome after murdering someone in a bet gone bad. His last four years were spent in Southern Italy and Malta on the run. He died after a short illness at the age of 37. He had no students but many followers.

General Art History Sources

Harris, Ann Sutherland. Seventeenth-Century Art and Architecture. Second Edition. Prentice Hall, 2008.

Hartt, Frederick and David G. Wilkins. History of Renaissance Italian Renaissance Art. Seventh edition. Prentice Hall, 2011.

Paoletti, John T. and Gary M. Radke. Art in Renaissance Italy. Fourth edition. Laurence King, 2011.