Venice in Six Iconic Symbols

- Gerriann Brower

- May 9, 2022

- 14 min read

Updated: Jun 13, 2022

Visitors to Venice five hundred years ago surely walked across the Rialto Bridge, possibly purchased a book, rode in a gondola, saw numerous winged lions atop structures, and drank water out of beautiful glassware. Each of these places and items are iconic parts of Venetian history, pieces of a historic puzzle of its faded, but still very visible past.

Glass

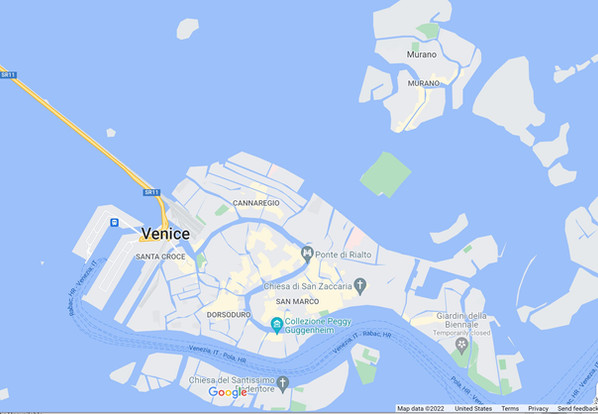

Venice, specifically the island of Murano, is synonymous with glass. If you walk the streets of Venice today, or in the fifteenth century, glass objects are everywhere. The creativity, entrepreneurship, and tightly controlled political environment made Venice the European glass capital from 1450-1650. Although glass is sold more today as collectable art objects (and very expensive), hundreds of years ago glass dishes, window panes, vessels, plates, jewelry, and of course beverage glasses, in all shapes, sizes, and colors, were part and parcel of Venetian homes, especially the nobility. Patricians loved displays of wealth, and glassware became the perfect object for show.

Murano glass became the marque glass for Venetian export, with its finely crafted and imaginative techniques. Collaboration among artisans was common, and there were no secret recipes in Murano. When one shop fashioned a new technique or color, other makers adopted it. The goal was market domination, not internal competition. Shape, form, transparency, and brilliance were the trademarks of Venetian glass. The factories were made up exclusively of glass makers, as no other artisans were needed. It was a closed glassmaking business empire.

About 1450 Venetian glassmakers invented cristallo, a virtually transparent and spotless glass which became highly desirable in Europe and elsewhere. They also invented, or re-invented, a whitish glass called lattimo, and chalcedony glass, made to look like agates. Glass had three values in Venice, as a trade, art, and industry. It was useful in everyday life and a hot commodity. Documents show that glass beads, drinking glasses, plates, beakers, window glass, mirrors, jewelry, and other household items were exported en masse all along Venetian trades routes from the Dalmatian coast, to Greece, and Syria.

Murano wasn’t the only glass manufacturing site. Other Venetian controlled cities also made glass: Padua, Vincenza, and Treviso. The Murano furnaces were closed by law from July-October, so workers often migrated to other towns for work. During Venice’s glass monopoly era artisans did move from town to town and worked in different factories.

This example of chalcedony glass is free-blown (as was all Venetian glass). The unique colors are achieved by adding metallic oxides into the glass mixture prior to blowing the shape. This effect was invented in Murano in the late 1400s. This footed bowl, called a coppa, is about 5 by 7 inches. Because of their highly skilled and resourceful techniques, Venetian glassmakers were also excellent at forging precious gems.

Wells

Surrounded by lagoons and connected by about seventy islands, Venice is uniquely situated as a port on the Adriatic. Venetians were good problem solvers, and one problem they had was that there was water all around, but it wasn’t drinkable.

They depended on cisterns, mostly underground, to collect rain water for everyday use. In times of drought, barges brought water in from the nearby Brenta river. Wellheads were made to draw the water out from the cisterns. And in typical Venetian style, they made wellheads into works of art.

During the Renaissance about 7,000 wellheads served the population of about 190,000. Many were in public areas, in the squares, or campi, outside of churches. Many were private. Stone gutters channeled the precious water into terracotta or glass drainpipes which fed into the cisterns. Clay-lined cisterns were about ten feet deep and filled with sand to filter the water. Private wells were situated beyond a long corridor in a courtyard. Because the wells were essential to life in Venice they were locked down at night. There were severe fines and punishments for contaminating or polluting the wells.

Only about twenty wellheads remain in Venice today, and the Ca’ d’Oro palace has an outstanding example. It is unusual to know the maker of such an object, but in this case, we know Bartolomeo Bon sculpted the wellhead in about 203 days for the Contarini family. His father worked on the Ca’ d’Oro (ca’ is short for casa or house), and his sons followed him in the family business. The Ca’ d’Oro, which means house of gold, was in its heyday one of the most impressive palaces on the Grand Canal.

Bartolomeo decorated three sides with the Cardinal Virtues of Fortitude, Justice, and Charity, and left the remaining side for the well drawing device. Square at the top and round at the bottom, the wellhead mimics a capital. It is made of a pinkish-red Verona marble. Father and son worked on the architectural details of the Ca’ d’Oro, including the decorative elements surrounding the windows, trim, capitals, and cornices.

Venetians depended on this system of water until an aqueduct was constructed in 1884. Napoleon removed most of the decorations for his own enjoyment. Other remaining wellheads were sold to museums, including the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Wellheads also became a popular item to fake and sell as originals.

Books

Books are not something usually associated with Venice today, but they are an important part of its cultural and economic history. There are few inventions that caused Europe to change course in everyday life. The creation of movable type by the German Johannes Guttenberg in 1450 was one of them, and Venice seized the opportunity to become the printing capital of Europe. Prior to Venice, Ulm and Augsburg, Germany were the Northern European printing capitals. To grasp the enormity of this invention, pause to consider this: about the same number of books printed between 1450 and 1500 were equal to the number of books produced previously in the history of the world prior to 1450. The number of books published grew exponentially with each passing decade in the sixteenth century.

Instead of oversized and heavy tomes that were hand copied, there were now smaller paperback sized books readily available to the public. Many Venetians were literate as reading and writing were an important skill to run trade businesses. The University of Padua, only about 25 miles away, served to educate the nobility. According to one inventory of homes, about seventy percent of rich or middle-class homes owned books. Private libraries were common. Building a library of books was in vogue and a way to put on display the family’s education and wealth. Books included the Bible, plus translated Roman and Greek literature, poems, romances, poetry, and theatrical works. Libraries were not only for men as many women owned books.

Venice’s proximity to the eastern trade routes and Northern Europe meant books were printed for their intended markets in Hebrew, Italian, Greek, Spanish, Arabic, Latin, and Slavonic languages. At first printers were Germans working in Venice but soon Venetians dominated the industry, producing an estimated eighteen million copies in the sixteenth century.

The Malèrmi Bible (below) is typical of a fifteenth century Venetian book. Each page is approximately 8 x 11 inches with woodcut prints that are hand colored. It is remarkable that it survived and that we know the printer and publisher. It is called the Malèrmi Bible based on the translator Niccolò Malèrmi. These pages are open to the Book of Proverbs printed in the vernacular Italian. Some pages are full color illustrations. This Bible was intended for everyday use by a middle-class family, and would be a pleasure to read. There are different volumes of the Malèrmi Bible, some with up to 430 woodcuts.

The Rialto

The gracefully arched Rialto bridge crossing the Grand Canal is found on many souvenirs and is a crowded mecca for those hoofing it from the train station to San Marco. It is a must-see for those traveling by water or on foot. Most stop to gawk at the Grand Canal, take the selfie, and move on without pausing to think what this bridge might have meant in Venice’s history.

Originally a wooden bridge, it contained a draw bridge hoisted up to allow the large galley ships to pass through. The Rialto is first documented in 1097 as a merchant center. Antonio da Ponte designed and built the current version from 1588-91. His name is appropriate as ponte means bridge in Italian. It was the only bridge to cross the Grand Canal until the 1850s.

The Rialto is more than a bridge, because it refers to the surrounding commercial area and neighborhood. It remains a hub from the Middle Ages on. This area was chosen as the market center and canal crossing as it was the highest marshy area along the canal and for its access to and from the sea. Prior to the 1500s ships coming in from trade routes unloaded at the Rialto; later on, they unloaded where the water meets land at the Doge’s Palace. The bridge was lined with markets and the neighborhood sold imports from over the world even after the ships changed their unloading zone.

Venice started trading with the east in 700 and dominated the eastern routes for hundreds of years. By 1000 Egypt, Syria, Tripoli, and Alexandria were partners in trade and later on, Lebanon. Spices, dyes, pigments for paints and dyes for textiles, cotton, paper, textiles, antiquities and other luxury goods were imported. Venetians exported glass, books, soap, paper, wool, and other textiles. Shops spilled out onto the adjacent alleys and streets, selling all sorts of items. Negotiation and competition were sharp. Dealers in rare eastern luxury items were well-connected with numerous buyers and sellers. If important guests visited Venice, special tours were organized in the market areas.

Since Venice had no legitimate Roman ruins or history, items from the Roman era, especially sculpture, were in demand. Antiquarians specialized in such finds, as well as other odd items for rich clientele. One such dealer procured a unicorn horn from Lviv, Ukraine, which he tried to peddle to the Medici in Florence. The seller claimed the horn was intact, fragrant, and translucent. One of a kind! We don’t know if the Grand Duke of Tuscany purchased the horn, but he may have balked at the 8,000 scudi price. (A stonemason would make about 84 scudi a year.)

The Rialto area was also the official government sanctioned area for brothels. Women were allowed to run the brothels and the government tried, mostly in vain, to limit the prostitution business. No matter how one looks at this, it was human trafficking and exploitation. The view of government and of the nobility was that prostitution was an evil to be tolerated and served a purpose to protect the gentile chastity of Venetian women from aggressive male carnal desires.

Gondolas

In Venice there are only two ways to get around: on foot or on water. In the past, if you were poor, you walked. If you were middle or upper class, you had a gondola. There were hardly any horses on land, but a lot of human powered carts and wheelbarrows. Gondolas are long flat-bottomed boats, without a rudder, propelled with a long oar made of beechwood. Most gondolas had two gondoliers for propulsion, one in front and one in back. The canals are about seventy feet deep, so gondoliers today need to carefully traverse wakes from motorboats, and the large water buses called vaporetti. Before the gas driven boats, there were an estimated 10,000 gondolas in Venice’s heyday. Today there are hundreds for tourists. Gondolas are still repaired in a small squero, or shipyard, by the church of San Trovaso.

The Venetians leaned heavily towards displays of wealth and consumerism, but very light on employing servants. An exception were the gondoliers, who were servants for the nobility, in service for everyone to see that the family had a gondola and a boatman. Gondolas by law have been painted and varnished black for centuries in an effort to downplay wealth, however, Venetians found a loophole and used expensive tapestries to drape over the benches. Nowadays gondolas are open, but previously they had enclosed cabins so people couldn’t see who was riding, or what might be happening inside.

Not all gondoliers worked for a private family. Some gondoliers were independent (like Uber) and owned their boats, and some purchased them from their employer. It was considered a lower-class job. Some were ferry gondoliers which transported people back and forth across the Grand Canal and were indebted to no particular family.

Gondolas used to come in all sizes and shapes, and as well as large galley ships, war ships, and merchant ships. There was also the gilded limousine of gondolas, called the Bucintoro, which was used for transporting the Doge, or brought out on festive or religious occasions when ambassadors, popes, or kings visited Venice. It was quite a procession with a series of large galley ships and hundreds of other boats. Ascension Day was a particularly important religious holiday for the Venetians, when the city celebrated a mystical marriage to the sea. The Ascension celebrates Jesus’ ascent to heaven forty days after the Easter Resurrection. A grand procession included the Doge tossing his ring into the lagoon as a symbolic gesture.

There was a festive market celebration in the square of San Marco. In this painting by Canaletto the Doge (under an umbrella) approaches the Bucintoro in an area called Il Molo, a paved area open to the water. Prior to the railway, this would have been the first impression a visitor had of Venice. The Doge’s Palace is in the center of the painting, with the bell tower to the left. The boats, water, and palace are the most dominant features, while the people are dwarfed by the size and splendor of the Bucintoro and the buildings.

Today Venetians hold a Regata Storica in early September, an historical regatta of sixteenth and seventeenth century boats. This grand event is based on rowing competitions and parades started in the fourteenth century. Every vessel is decorated. Boats are rowed standing up as they proceed down the Grand Canal with competitions based on the number of rowers.

The Winged Lion

Approaching the Doge’s Palace from the water is as impressive today as it was nearly eight hundred years ago. The pinkish palace gives way to the large piazza of San Marco. Greeting all visitors before the palace are two tall columns. One has a winged lion fiercely staring out at the sea. As one walks towards the church of San Marco and the piazza there are at least eight other representations of the winged lion on the fronts of buildings, atop flag poles, and at the apex of the belltower.

St. Mark is the patron saint of Venice and his symbol of the winged lion is found everywhere in the city. Each evangelist has an animal symbol, usually depicted with wings. Winged angels or winged animals as symbols of the evangelists represent their divine nature.

The legend of the saint from his ministry in the first century and how Venice claimed him as their protector is fascinating. Mark, one of the gospel authors, was said to have been sent by St. Peter to spread the word to the peoples of Aquileia. Aquileia was a Christian community formed on the northern reaches of the Adriatic Sea, close by to present-day Slovenia. It was a prosperous region and existed before Venice was founded.

Legend says Mark was shipwrecked in the lagoons surrounding Venice on his way to Aquileia when an angel took the form of a winged lion to tell him his final resting place would be in Venice. He survived the ordeal to arrive in Aquileia and continued his ministry there. Later on, he traveled to Alexandria, a seaport in present day Egypt, where he became bishop. Mark was martyred and buried there in a church. Later, when Attila the Hun invaded from the North, the Aquileia peoples fled and many ended up on the islands of the Venetian lagoon, essentially settling the islands what we now know as Venice, Torcello, Murano, among others. Venice was founded by refugees. Aquileia diminished in power as Venice grew in influence.

It is not surprising that Venetians believed that Mark’s relics were pre-ordained to be in Venice, not Alexandria. They felt a strong need to repatriate the body to Venice. There was also the issue that Egypt was Muslim and Christians would want his body in Christian territory. Again, relying on legend, two Venetian merchants in Alexandria collaborated with two priests to steal the body from the church and bring it back in 829. This was considered a form of rescue, not theft. There’s even a work for it: translatio, the transfer of a holy relic to its proper place for veneration. The four rescuers removed the stone tomb cover and carefully removed the body, which was wrapped in silk, with various seals to prevent just such a thing from happening. They deftly replaced the body with a different saint, affixed the seals, and closed the tomb.

According to Catholic belief, martyrs and saints do not decay, they are incorruptible, remaining intact for hundreds of years, if not forever. Instead of a decomposing in a putrid smell, they give off a sweet scent, which proved to be an issue for the four rescuers. Mark smelled so good and strongly that people had noticed as they transported the body out of the church and made their way to the port. They got the body to a ship, but the Muslim inspectors were on to it. They hid the body in a barrel of pork, which put off the inspectors, as pork is unclean meat for Muslims. Mark and the four men made it back safely to Venice, surviving various storms, which were considered justification for their brave rescue. When they arrived in Venice the saint’s body was received with great celebration. Aquileia felt they had been a more deserving resting place for St. Mark’s body, but the more powerful Venice won out.

Doge Giustiniano immediately began to construct a chapel to honor the saint, which eventually over the centuries became the Basilica of San Marco, with its wonderful mosaics. There were a number of additional holy events validating the importance of transporting Mark to his resting place – including stories about Mark resting at the Rialto (which wasn’t even built yet) on his way to Aquileia, visions, and miracles. St. Mark, in the image of a winged lion, became the symbol of Venetian pride and determination.

The winged lion represented Venice’s dominance over the Adriatic Sea, trade routes, and prosperity. The lion is shown either in a defense stance with a sword or with the gospel book. Today, St. Mark’s winged lion appears on the Italian naval and merchant ship flags. The Venice Biennale juried international modern art show takes place in the spring and fall of each year. The jury awards a Golden Lion to various artists, and the winners receive a golden statue of a winged lion to commemorate their talents.

Winged Lion, around Piazza San Marco, photos Gerriann Brower.

If you go to Venice

Venice has struggled for years to cope with mega tourism, cruise ships damaging the lagoons by San Marco, and day trippers. The pandemic gave the city pause to implement measures to manage the number of tourists. Thirty million people a year visited Venice in 2018. There are only about 50,000 permanent Venetian residents, a number that has steadily declined due to the expense of living in the city.

Starting in June 2022 visitors not staying overnight in Venice will have to pay a fee (up to 10 Euro) and pre-book on an app to enter the city. This is a six-month trial after which Mayor Luigi Brugnaro will evaluate and possibly implement city wide in 2023. CCTV cameras will monitor people and water traffic to detect when there is overcrowding and manage the flow of tourists. Over seventy percent of visitors are in Venice for one day only and don’t contribute as much to the economy as those who stay overnight.

My advice: avoid Venice June-August. Spring and fall, and visiting early in the week are better options. Ask yourself, what kind of experience do I want? How do I want to remember my time in Venice? By all means see San Marco, its square, the church and Doge’s Palace. It is truly spectacular. Try to get away from the Rialto and San Marco areas to explore some quiet, great neighborhoods, like Castello or Cannaregio, and pop into some churches for art. There are many great museums without large crowds. Stroll along the smaller canals away from the Grand Canal, or for a memorable experience, take a private water taxi down the Grand Canal or around the main islands.

Sources

Burkart, Lucas. “Negotiating the Pleasure of Glass: Production, Consumption, and Affective Regimes in Renaissance Venice.” Materialized Identities in Early Modern Culture, 1450-1750: Objects, Affects, Effects, edited by Susanna Burghartz, et al., Amsterdam University Press, 2021, pp. 57-98.

Brown, Patricia Fortini. Art and Life in Renaissance Venice. Laurence King, 1997.

Brown, Patricia Fortini. Private Lives in Renaissance Venice: Art, Architecture and the Family. Yale University Press, 2004.

Brown, Patricia Fortini. "The Aesthetics of Water: How Venice Conquered the World." April 18, 2018, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Guest Lecture.

Clarke, Paula C. “The Business of Prostitution in Early Renaissance Venice.” Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 68, no. 2, 2015, pp. 419–64.

Damen, Giada. “Shopping for Cose Antiche in Late Sixteenth-Century Venice.” Reflections on Renaissance Venice: A Celebration of Patricia Fortini Brown, edited by Blake de Maria and Mary E. Frank, Harry N. Abrams, 2013, pp. 133-141.

Gudenrath, William. The Techniques of Renaissance Venetian Glassworking. Corning Museum of Glass, 2019.

Howard, Deborah. The Architectural History of Venice. Yale University Press. 2002.

Howard, Deborah. Venice and the East: The Impact of the Islamic World on Venetian Architecture 1100-1500. Yale University Press, 2000.

Madden, Thomas F. Venice: A New History. Penguin Books, 2012.

McGreevy, Nora. “Starting Next Summer Day-Trippers Will Have to Pay to Enter Venice.” Smithsonian Magazine, August 27, 2021.

Romano, Dennis. “The Gondola as a Marker of Station in Venetian Society.” Renaissance Studies, vol. 8, no. 4, 1994, pp. 359–74.

Schulz, Anne Markham. “The Sculpture of Giovanni and Bartolomeo Bon and Their Workshop.” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 68, no. 3, 1978, pp. 1–81.

Scuro, Rachele. “Shaping Identity through Glass in Renaissance Venice.” Materialized Identities in Early Modern Culture, 1450-1750: Objects, Affects, Effects, edited by Susanna Burghartz et al., Amsterdam University Press, 2021, pp. 99–134.